The center’s not holding, it’s folding. How about rounding?

14 September 2025

William Butler Yeats wrote famously that “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold…” Accordingly, opinion writers, left and right, have been writing about the center holding or not. What center? Mostly it’s been folding, not holding.

Why do we tolerate the linear politics of left, right, and center? Has not two centuries since two groups happened to sit on the left and right sides of the French revolutionary assembly been long enough?

left ______________ center ______________ right

Much of politics these days swings like a pendulum, between government controls on the left and market hegemony on the right. As a consequence, the center becomes paralyzed, the country becomes ungovernable, and power shifts increasingly to the right. No wonder we get nowhere with our crises of climate change, income disparities, and the demise of democracy itself.

A society, like a stool, cannot be balanced on one leg, whether communism or socialism on the left or capitalism or populism on the right. Nor can it be balanced on two legs, namely back and forth between these two. A third leg is needed for stability, and progress.

To appreciate this, consider these three basic human needs: for consumption, supplied significantly by private sector businesses; for protection, served especially by public sector governments; and, no less fundamentally, for affiliation—for which we depend, not on government or business, but our families, and beyond that, our communities. The latter functions in another sector that has to be understood, for the sake of survival.

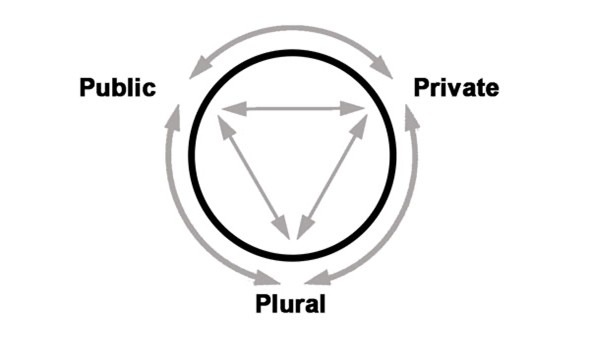

Formally, this sector is called “civil society,” a label whose ambiguity helps to explain its obscurity. So, too, do its variety of other confusing labels, such as the non-profit, non-governmental, and social sector. Calling “civil society” the plural sector can help to bring it out of its obscurity, not only to recognize its sheer variety of associations, but especially because this label can enable it to be seen as taking its place alongside those sectors called public and private—hence, to appreciate balance in society.

This third leg was recognized by Alexis de Tocqueville in the 1830s, when he wrote about community associations as a critical component of the new Democracy in America: “… civilization itself would be endangered” if people “never acquired the habit of forming associations…” Unfortunately, it is hardly so recognized today, despite being ubiquitous: it has been drowned out by the strident voices of the left and the right.

A healthy society balances itself on a public sector of respected governments, a private sector of responsible businesses, and a plural sector of robust communities. The latter is the sector of our social affiliations, whose associations are neither part of the state apparatus nor owned by private investors. Some are owned by their members, as in farmer cooperatives and credit unions, while many others are owned by no-one: think Greenpeace, Wikipedia, the Mayo Clinic, and more generally, foundations, food banks, community hospitals, and social movements. (Note that such associations exist across the political spectrum, from a Marxist cell to a rifle association.)

Where to put this plural sector on that line of linear politics? Certainly not at the center. We don’t need compromise between our basic needs—say, a little more consumption for a little less protection—so much as some sort of balance across them. Accordingly, let’s reshape our politics by rounding the line of linear politics—left, right, and center—into a circle, to understand how three fundamental sectors can cooperate for balance while holding each other in check.

How many plural sector associations have you connected with in the last few days? I’ll bet quite a few—working out at the Y, being treated in a community hospital, attending a meeting of some religious service, donating to a charity, maybe marching for a cause. Many of us may work in private sector business and most of us may vote for public sector government, but all of us live our personal lives significantly in this sector. The plural sector is our sector.

Mary Parker Follett wrote famously in the 1920s about three ways to deal with a conflict, two of which she dismissed. The first she called domination, when one side wins. The problem is that the other side “will simply wait for its chance to dominate.” We have seen enough of this, for example, in the shifts from one form of imbalance to another in Eastern Europe over the past century: domination by state communism or populist fascism followed by market capitalism now shifting toward dogmatic populism.

The second way she called compromise, wherein “each side gives up a little in order to have peace.” But with neither side satisfied, Follett contended that the conflict would keep coming back. (The conflict in the Middle East can be seen, like so many others, as between, not just Palestinians and Israelis, but the extremist and the moderates, with the extremists, on both sides, determined to dominate, without compromise. The moderates suffer the consequences.)

Follett thus favored a third option, which she called integration, where the two sides seek some common ground, based on a recognition of what they truly need.

“Integration involves invention…not let one’s thinking stay within the boundaries of two alternatives, which are mutually exclusive. In other words, never let yourself be bullied by either-or situation… Find a third way.”

Her example is a simple one. In a library, one person wanted a window open for fresh air while she wanted it closed to avoid a draft. So they opened a window in an adjacent room. This solution was hardly brilliant or particularly creative, just resourceful. All it took were open minds and goodwill.

Linear politics has become intrinsically confrontational, as each side seeks to dominate, or else reluctantly accept compromise—never ending. Circular politics can be seen as potentially more integrative, for example, in the form of private, public, plural partnerships. Today, we desperately need another way. The circle can be that. Here community associations can not only help to sustain balance, as de Tocqueville implied, but also play the leading role in attaining balance in the first place, by promoting resourceful solutions to our escalating crises.

The private sector will not do that, however fashionable “fixing capitalism” has become. Capitalism certainly needs fixing, not least in its myopic stock markets. But fixing capitalism will no more fix the broken societies of the West than would fixing communism have fixed the broken communist societies of Eastern Europe.

The Western societies need fixing, in part by putting capitalism back in its place, namely the competitive marketplace, where it functions best, and out of the public space, where it has become so destructive. Nor will government by itself be able to restore the necessary balance: in the center, it is too compromised, elsewhere, it is too partisan.

The evidence from major constructive social change suggests that reformation begins on the ground, with community movements that spread—“go viral”—eventually to drive governments to do what is necessary and businesses to do what is responsible. As Franklin Delano Roosevelt reputedly told a community organizer when asked to support his cause: “I agree with what you’ve said. Now go out and make me do it.” For the sake of survival, we may well have to rally around the circle, to make ourselves and our authorities do it.

____________________________________Henry Mintzberg, Order of Canada, is Cleghorn Professor of Management Studies at McGill University and the author of 21 books, including Rebalancing Society (that diagnosis the imbalance), as well as the website RebalancingSociety.org (that prescribes a path to balance).