Blog

Subscribe

Blog

This blog is about reframing management and lots more. It started as a TWOG (TWeet 2 blOG) but is now also a much LinkedIn 2 blog. Every few weeks, from pithy pronouncements in a line or few to playful provocations in a page or few. See the BLOGs directly (now numbering over 200 posts), connect to them via LinkedIn or twiXer, or subscribe on MailChimp.Categories

2 September 2014

18 December 2023

25 February 2022

9 March 2019

2 September 2015

23 May 2023

9 September 2022

7 December 2020

6 December 2020

17 October 2018

22 March 2017

16 June 2016

25 May 2016

7 April 2016

24 March 2016

14 January 2016

30 July 2015

23 July 2015

28 May 2015

21 May 2015

19 February 2015

31 October 2014

24 October 2014

26 September 2014

11 May 2023

27 January 2023

6 January 2023

17 November 2022

16 February 2019

18 November 2018

28 July 2018

2 June 2018

15 September 2017

3 June 2016

21 April 2016

14 April 2016

17 March 2016

10 December 2015

22 October 2015

1 May 2015

12 February 2015

5 February 2015

3 October 2014

19 September 2014

2 April 2025

1 April 2020

29 August 2018

24 August 2016

9 September 2015

9 July 2015

25 June 2015

26 March 2015

10 October 2014

23 September 2023

7 January 2022

4 October 2021

19 September 2020

7 December 2019

22 October 2019

28 January 2019

3 January 2019

16 March 2018

14 September 2016

5 November 2015

29 October 2015

11 June 2015

2 April 2015

2 April 2024

17 April 2023

19 February 2021

15 August 2018

31 March 2016

15 October 2015

5 March 2015

30 January 2015

21 November 2014

14 September 2018

23 October 2016

28 November 2014

19 March 2023

4 May 2017

22 February 2017

7 February 2017

1 July 2015

19 December 2014

12 December 2014

5 December 2014

10 April 2024

2 September 2020

2 April 2020

13 February 2018

18 May 2017

19 April 2017

27 July 2016

6 January 2016

24 December 2015

3 December 2015

26 November 2015

12 August 2022

24 June 2022

25 November 2021

7 March 2020

1 February 2020

1 January 2020

20 December 2019

4 October 2019

5 September 2019

16 August 2019

19 July 2019

4 July 2019

20 June 2019

30 April 2019

23 March 2019

2 October 2018

7 December 2017

6 July 2016

16 December 2015

23 September 2015

17 September 2015

27 August 2015

6 August 2015

20 January 2015

9 January 2015

2 January 2015

26 December 2014

14 November 2014

7 November 2014

17 October 2014

24 October 2025

25 January 2025

1 August 2024

2 April 2022

25 March 2022

27 October 2021

18 October 2020

5 August 2020

9 June 2020

8 June 2020

2 May 2020

1 May 2020

15 January 2019

15 January 2018

9 November 2017

29 July 2017

9 March 2017

26 January 2017

11 February 2016

18 June 2015

3 June 2017

4 October 2016

8 October 2015

31 October 2018

27 October 2017

17 April 2015

10 April 2015

8 April 2021

17 July 2020

8 December 2018

13 July 2018

17 May 2018

21 December 2017

2 September 2016

17 August 2016

20 August 2015

28 April 2016

10 March 2016

5 April 2020

4 April 2020

31 March 2020

7 June 2018

1 July 2017

22 June 2017

8 June 2017

20 January 2017

12 August 2016

14 July 2016

8 June 2016

24 February 2016

21 January 2016

12 November 2015

24 April 2015

14 September 2025

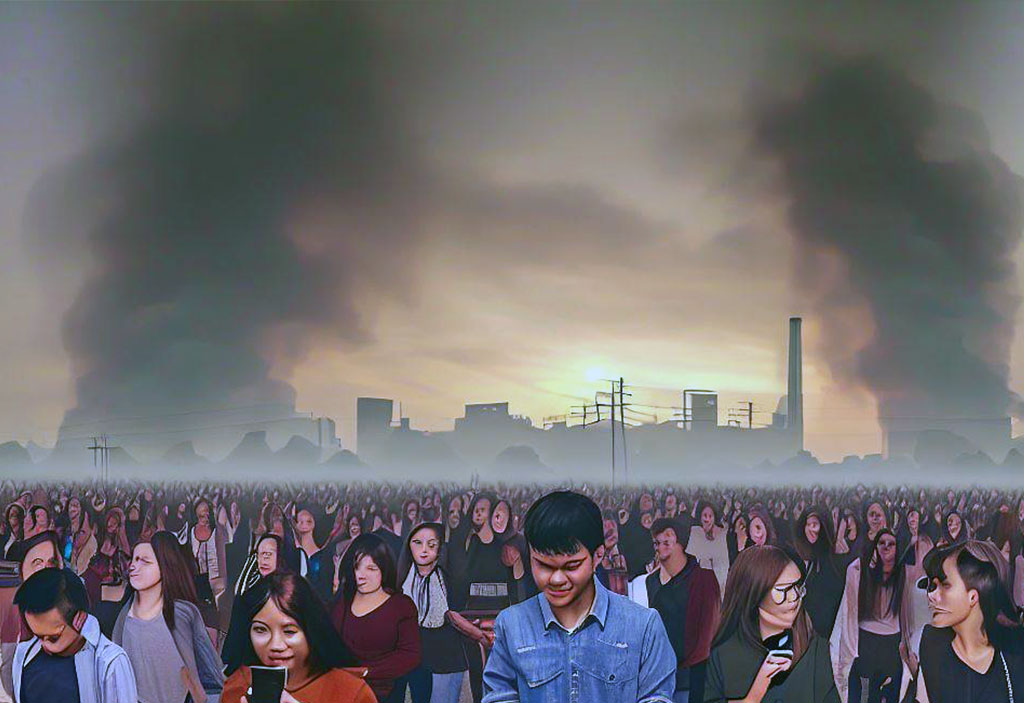

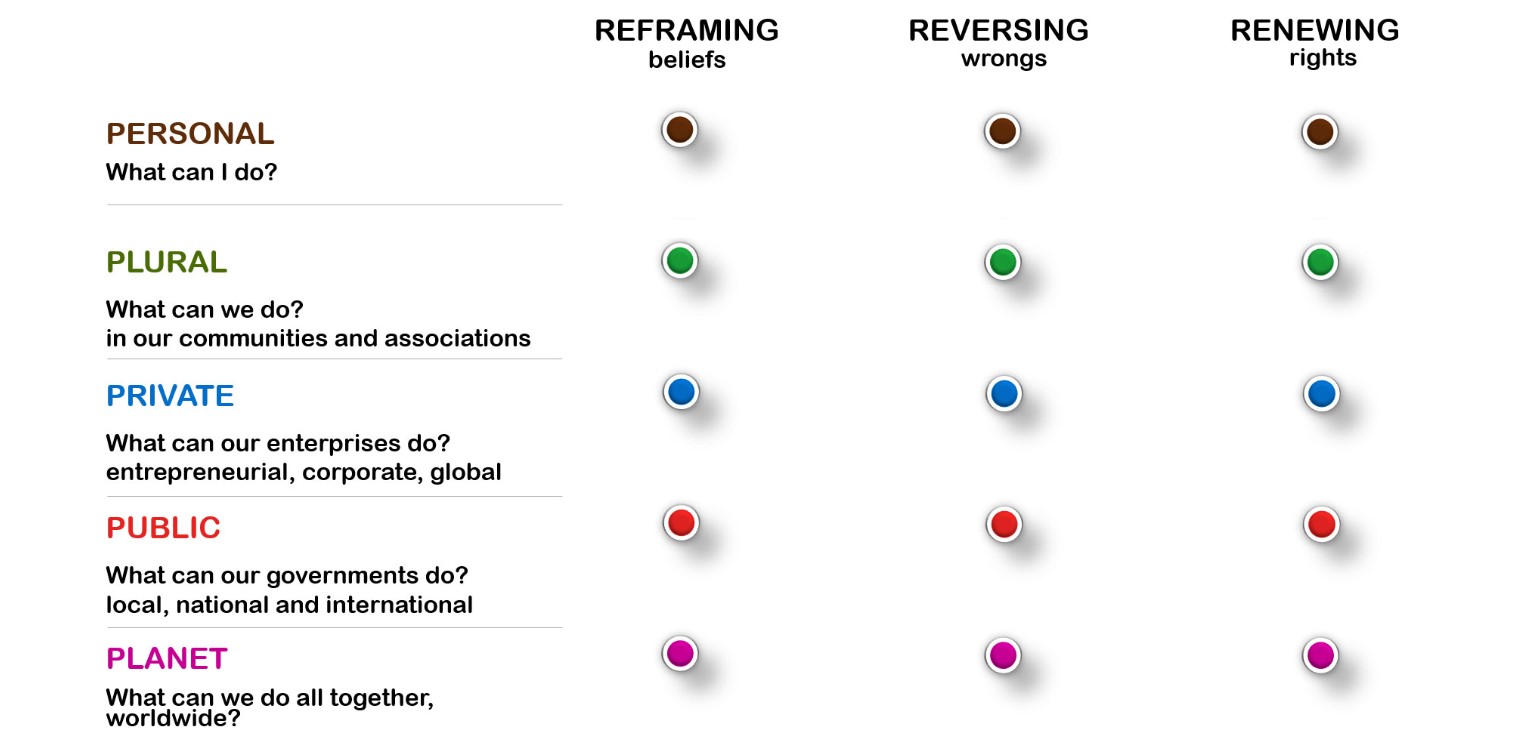

How many people do you know, yourself included, who want to do something about the dreadful state of the world but just don’t know where to begin? When Irene, for example, a Canadian finance manager, read an early draft of my book

How many people do you know, yourself included, who want to do something about the dreadful state of the world but just don’t know where to begin? When Irene, for example, a Canadian finance manager, read an early draft of my book

Welcome to the new space race. With catastrophic impudence, Bezos, Branson, and Musk claim to serve the world by dumping

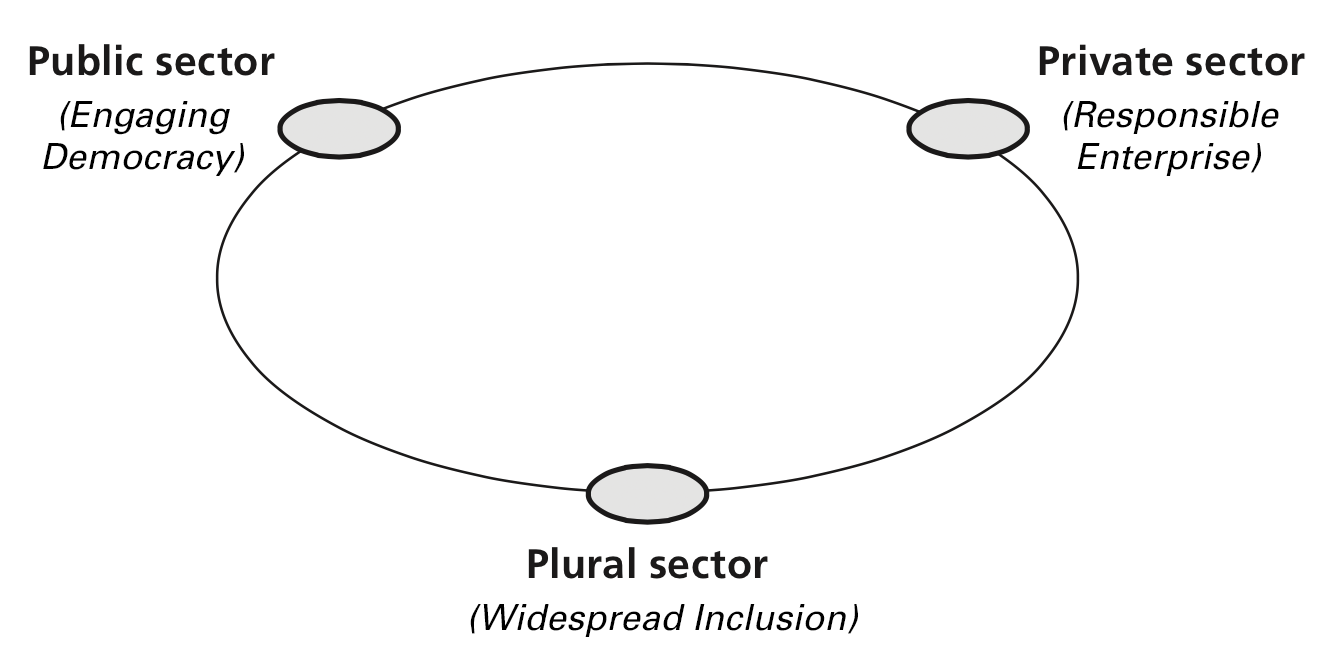

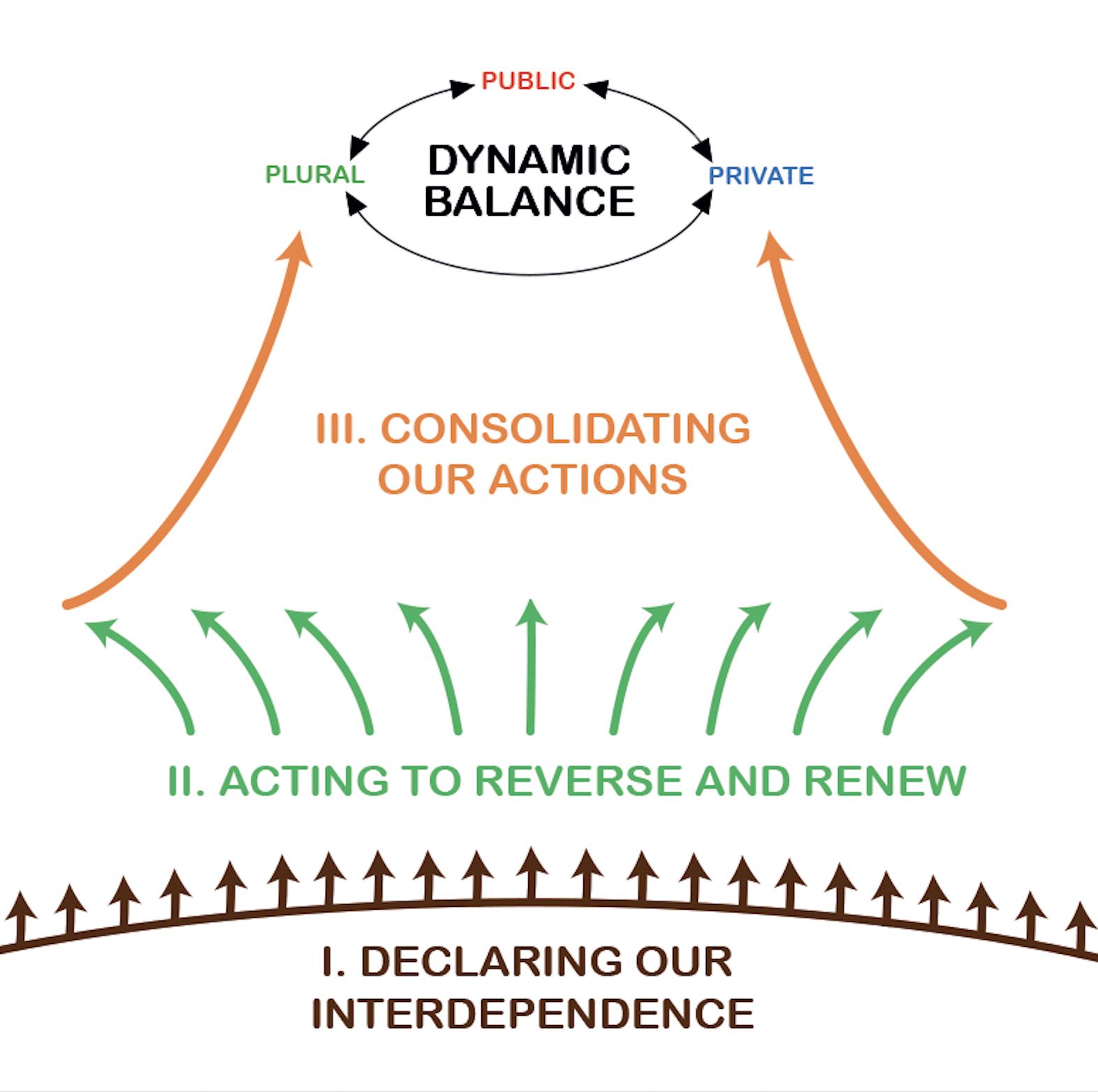

Welcome to the new space race. With catastrophic impudence, Bezos, Branson, and Musk claim to serve the world by dumping  Climate change is not the problem. It is a consequence of the problem. Our societies are out of balance, overwhelmed by rampant individualism and corporate entitlements. Until we recognize this, we will make no headway in reversing climate change. How many more COPouts will that take?

Climate change is not the problem. It is a consequence of the problem. Our societies are out of balance, overwhelmed by rampant individualism and corporate entitlements. Until we recognize this, we will make no headway in reversing climate change. How many more COPouts will that take?

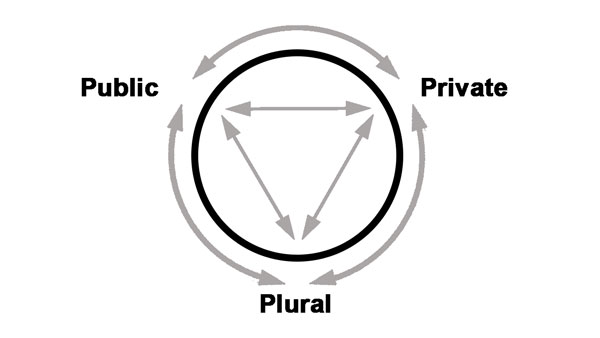

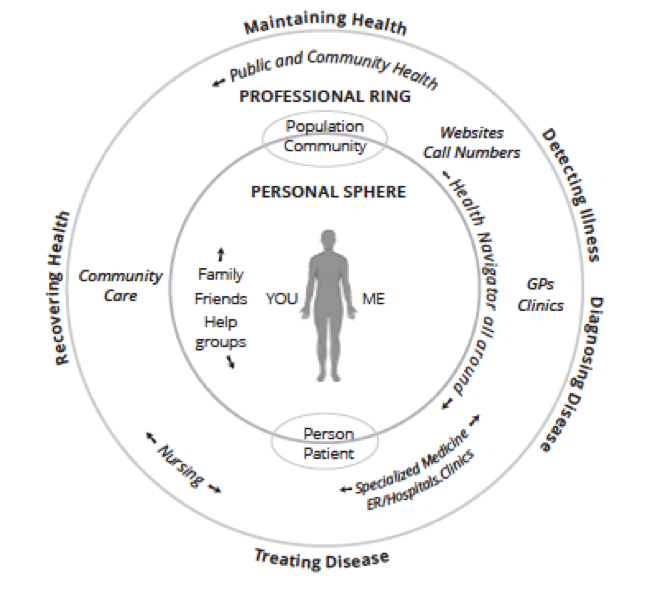

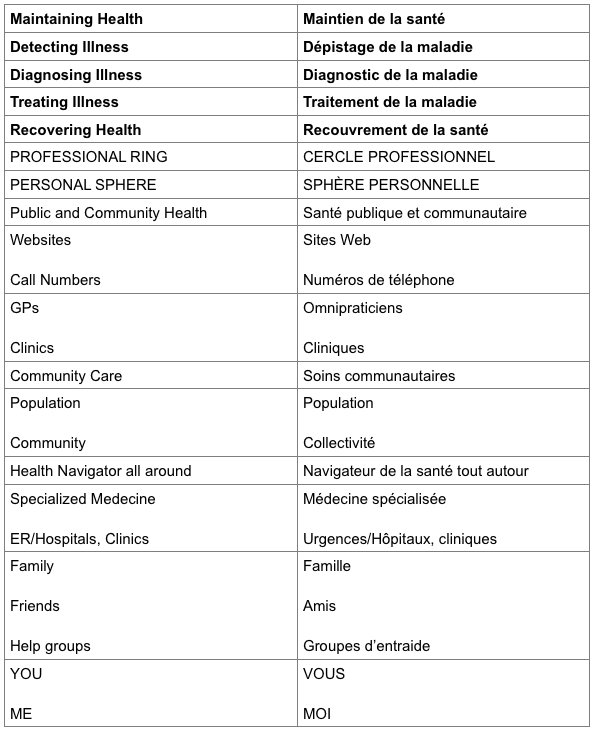

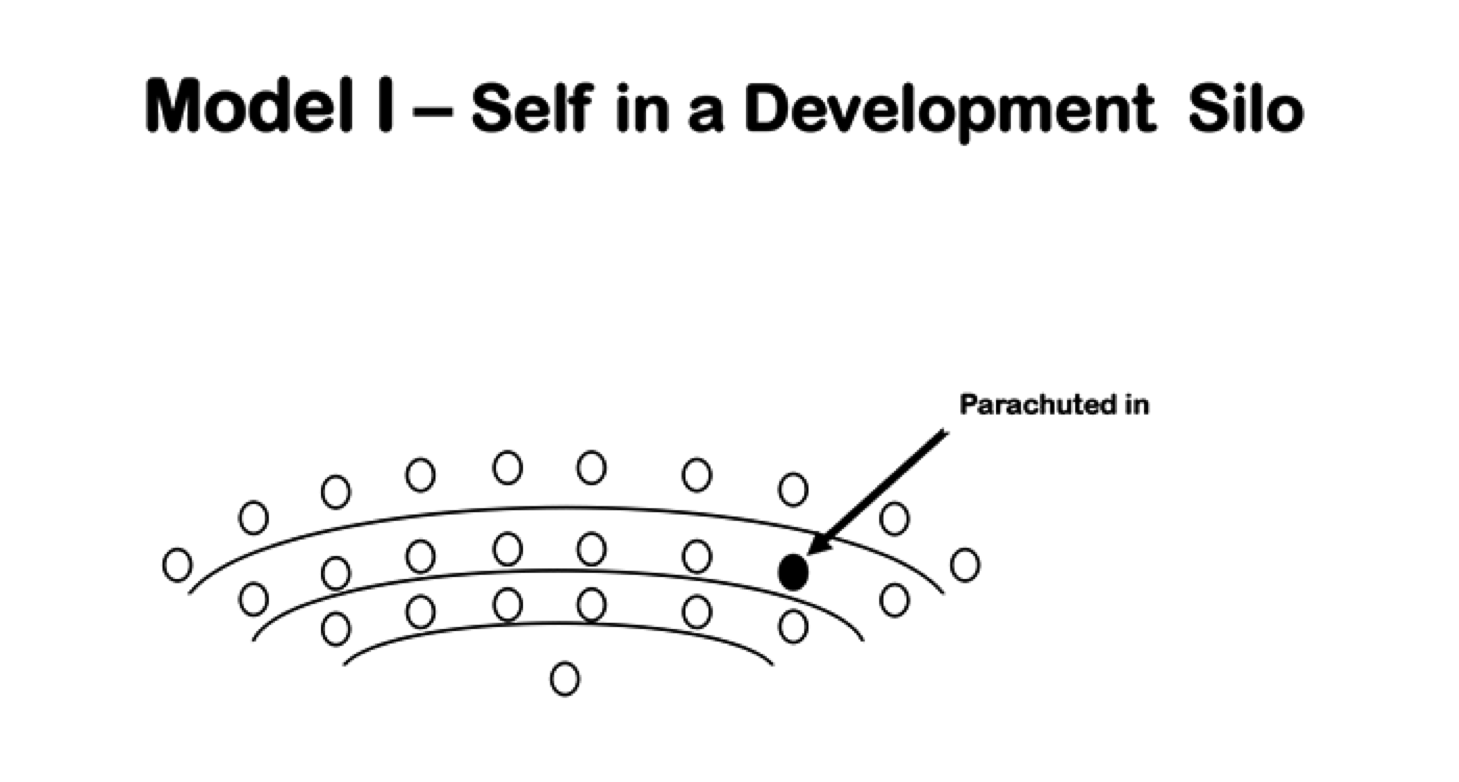

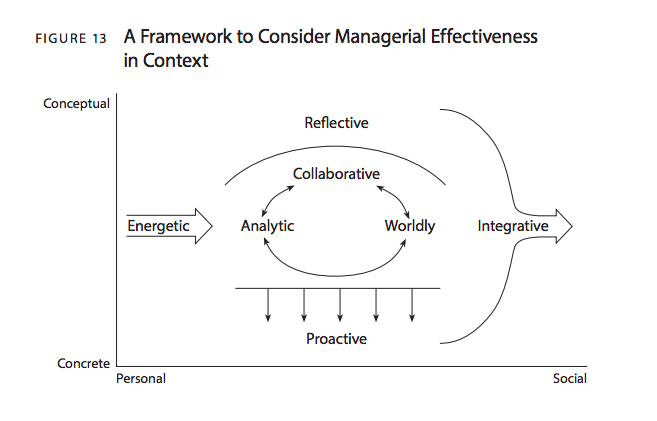

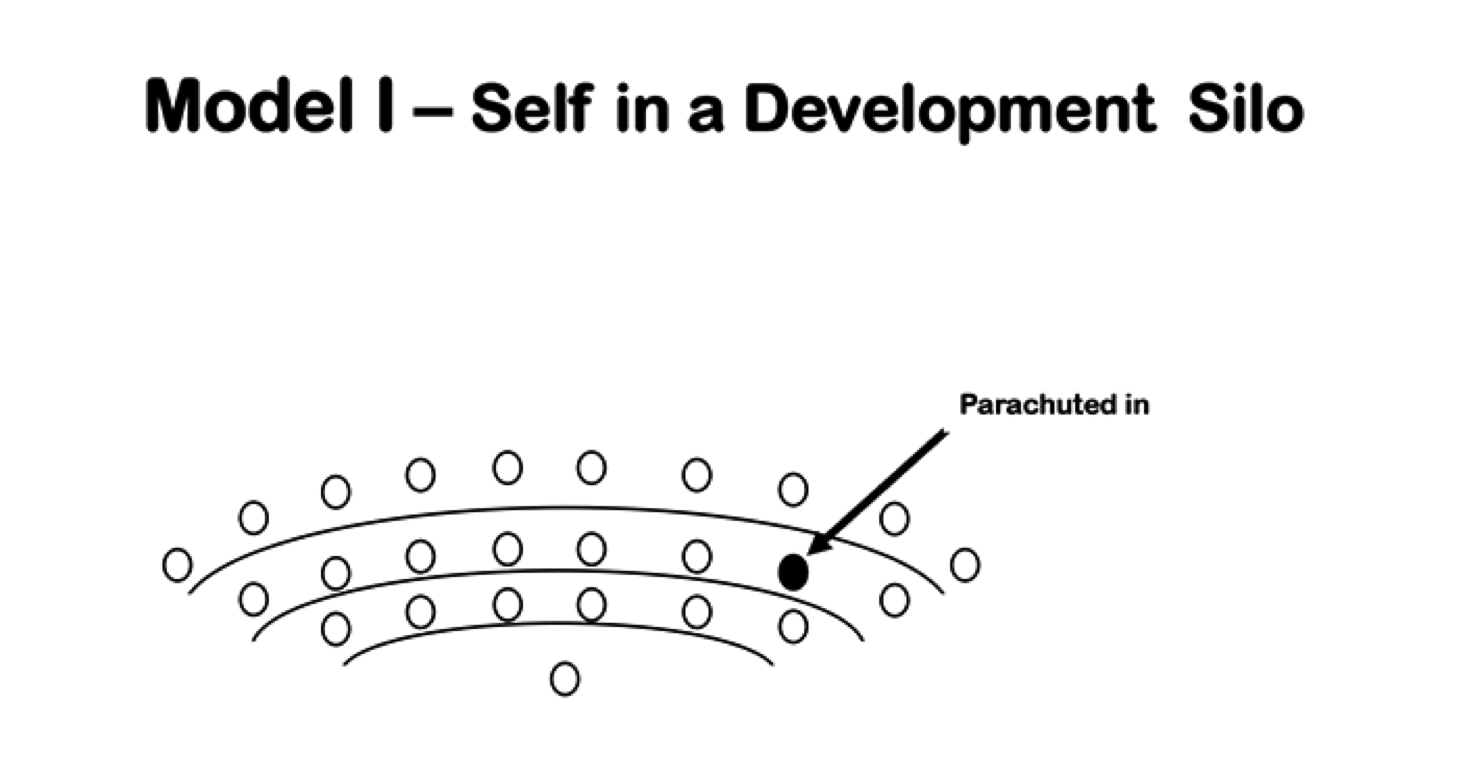

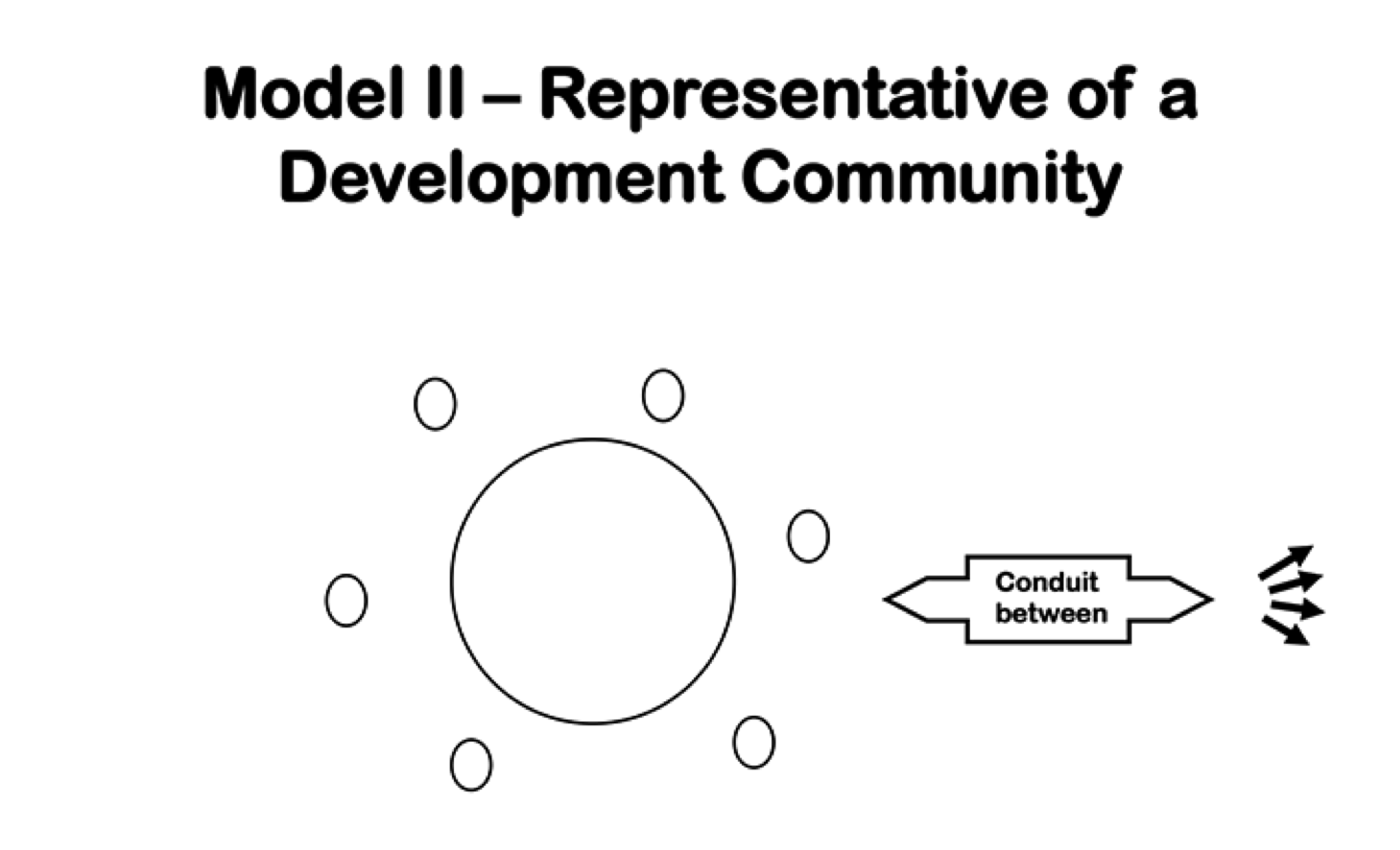

Courtesy of CoachingOurselves.com

Courtesy of CoachingOurselves.com

Courtoisie de CoachingOurselves.com

Courtoisie de CoachingOurselves.com

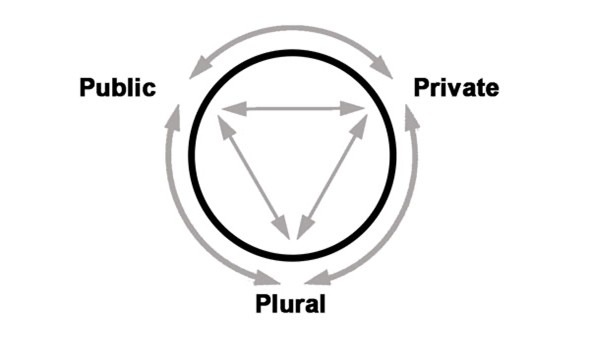

I posted this TWOG on 2 September 2016, quite auspiciously, and not only because it was the birthday of my blog (2 years old) let alone myself (older). I wrote that “maybe it’s time to look back and ask myself what all this has been about.” Or forward now, to ask what in the world is going on. Here was my answer in 2016, with minor editing now.

I posted this TWOG on 2 September 2016, quite auspiciously, and not only because it was the birthday of my blog (2 years old) let alone myself (older). I wrote that “maybe it’s time to look back and ask myself what all this has been about.” Or forward now, to ask what in the world is going on. Here was my answer in 2016, with minor editing now.

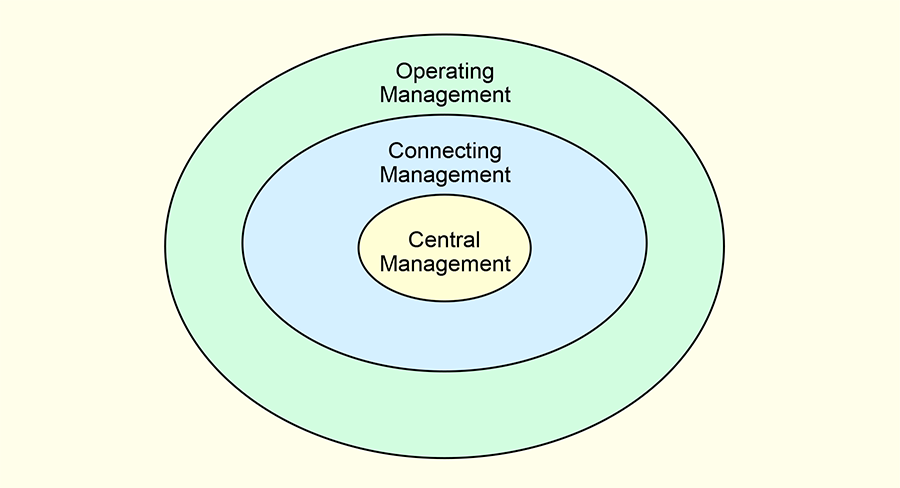

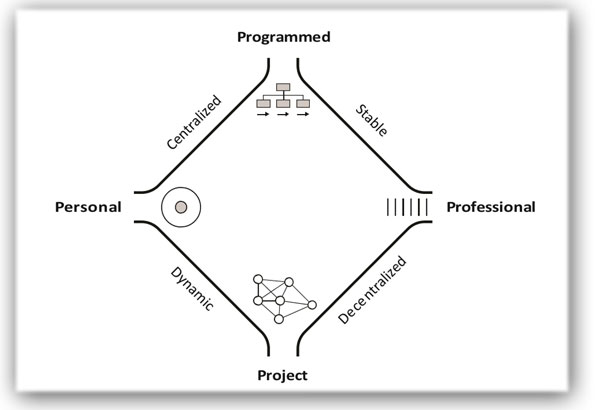

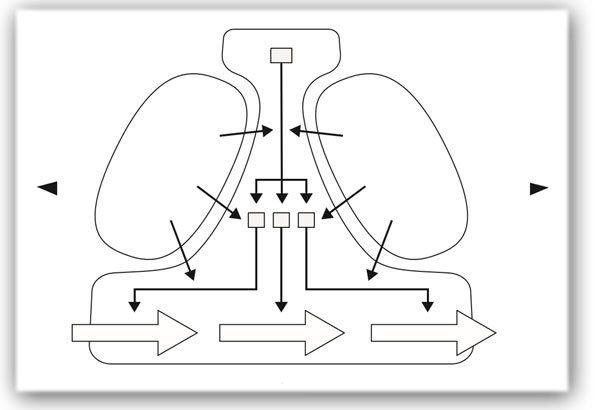

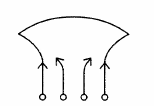

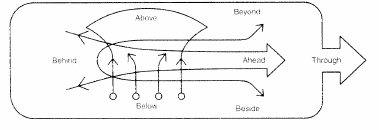

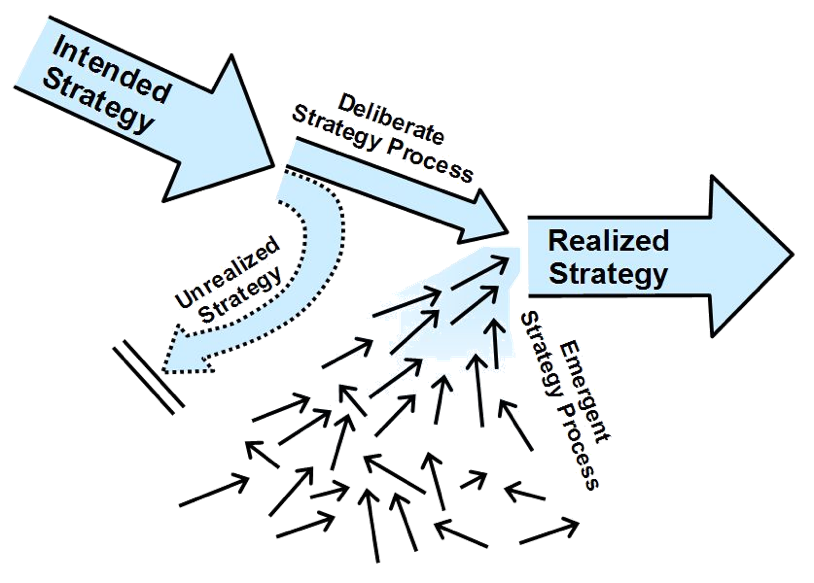

(diagram from Socket Software)

(diagram from Socket Software)

![Martin Luther [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.mintzberg.org/sites/default/files/512px-luther_95_thesen.png)

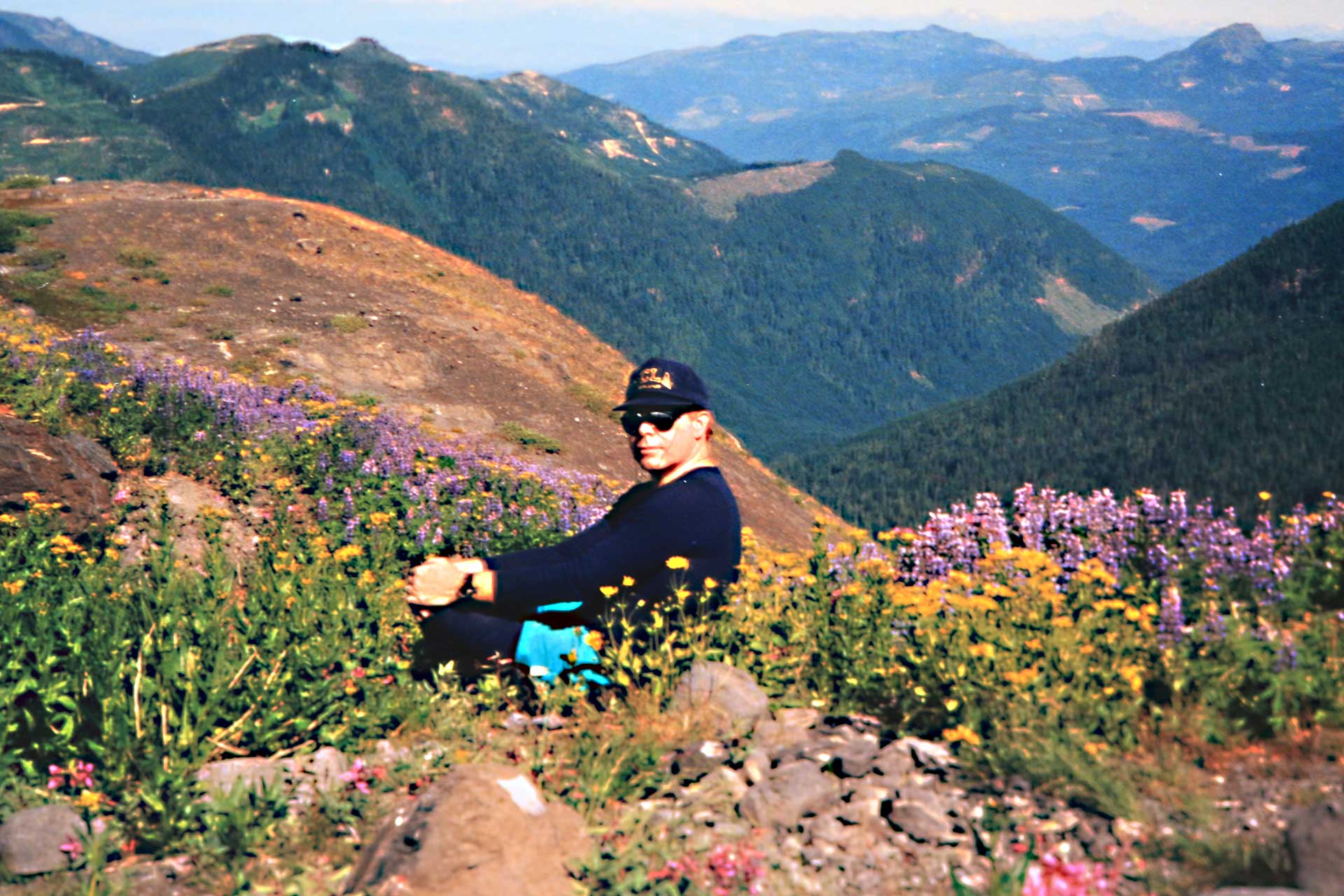

Hothouse Dick sitting among the weeds, photo by HM

Hothouse Dick sitting among the weeds, photo by HM La Malbaie: scene of the G7 meeting. Photo credit: Elaine Martin

La Malbaie: scene of the G7 meeting. Photo credit: Elaine Martin

Morning reflections in our IMPM module in Rio de Janeiro.

Morning reflections in our IMPM module in Rio de Janeiro.

Wallonian Farmer, photo by André Mouraux

Wallonian Farmer, photo by André Mouraux

We are masters at running successful experiments in failed events. On Wednesday, as part of the World Social Forum in Montreal, our event in the McGill University football stadium was entitled “

We are masters at running successful experiments in failed events. On Wednesday, as part of the World Social Forum in Montreal, our event in the McGill University football stadium was entitled “

Henry watching the mainstream going over a cliff. Or is it Lisa, his daughter who takes the photos, warning him about going over that cliff?

Henry watching the mainstream going over a cliff. Or is it Lisa, his daughter who takes the photos, warning him about going over that cliff?

Politicians Pledging in Paris

Politicians Pledging in Paris Markets barreling ahead

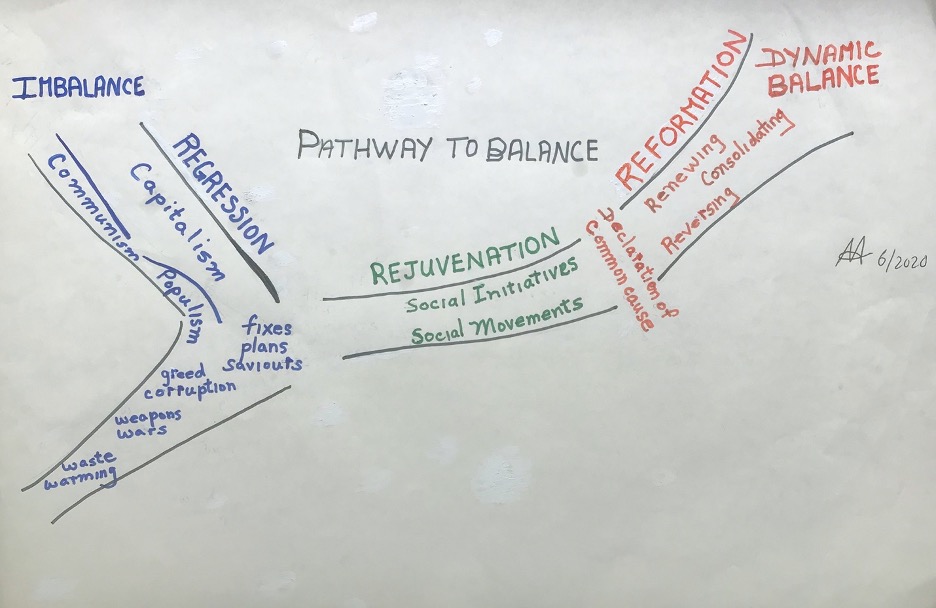

Markets barreling ahead Facing the issue of imbalance last week in our program

Facing the issue of imbalance last week in our program  Progeny on the planet

Progeny on the planet Mount Royal from my Montreal office. Sorry about what Santa, my assistant, calls our stained glass windows. They are not cleaned in the winter.

Mount Royal from my Montreal office. Sorry about what Santa, my assistant, calls our stained glass windows. They are not cleaned in the winter.

The Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution gives the people of America “the right to keep and bear arms.” This has helped those people who make and sell arms to make lots of money, the consequences be damned. So here is a conversation I fantasize having with the people at the National Rifle Association.

The Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution gives the people of America “the right to keep and bear arms.” This has helped those people who make and sell arms to make lots of money, the consequences be damned. So here is a conversation I fantasize having with the people at the National Rifle Association.